|

I have recently returned from the USA, where I gave a lecture at MIT on the architectural photographer Eric de Mare, accompanying an exhibition currently showing (until April 8) in the Wolk Gallery in the MIT main building on Massachusetts Avenue. Nearby was some highly interesting modern architecture both at Harvard and MIT- Le Corbusier's Carpenter Center, Frank Gehry's Stata Center, and the highspot- seen on a day with sunshine and deep snow- Eero Saarinen's MIT Chapel completed in 1955 and which I scarcely knew.  Saarinen is not much discussed now, but was one of the leading architects in the USA in the 1950s, having emigrated from his native Finland to the USA as a teenager in 1923. It's clear he brought something of a Scandinavian sensibility with him- the undulating walls of rough brickwork for one thing- and the overall effect of this small windowless space is powerful and dramatic, with light coming down to the altar through the cascading sculpture of Harry Bertoia. There's something space-age about it too- and this reflects the preoccupations seen in his best-known works, the terminal at JFK Airport originally built for TWA and the great parabolic arch at St Louis.

9 Comments

There's a lot of recent architecture in Japan that has been highly interesting to those in the West- and the idea that Japan had developed its own version of Modernism has been around since (at least) Kenzo Tange's work in the 1960s. While the combination of a sense of the austerity and compositional clarity of Japanese traditional architecture has been seen as a forerunner of modernist concerns for a much longer period- Frank Lloyd Wright and Walter Gropius were both suitably inspired, and wrote on the subject. The work of Tadao Ando can be seen extensively in Japan, particularly in the area of Kansai around his home city of Osaka. His work is often described, not least by him, as translating a Japanese sense of space, or perhaps more accurately a Japanese existentialism, into modern materiality and abstract geometry. Certain smaller projects, such as the Lotus Temple on Awaji Island, are highly inventive in their design and very powerful in their effect. Others, such as the nearby Yumebutai development and park, seem to be a repetition of themes he's done better elsewhere. Kengo Kuma, even though he is also well known and has also worked in Europe, is not necessarily as well regarded. But the Nezu Museum in Tokyo, set in a garden-oasis in the fashionable district of Aoyama, is delightful. It seems to be a less ponderous version, literally and figuratively, of a current interpretation of Japanese-ness, simple and understated, connecting with that tradition quite directly.

I have just returned from a first trip to Japan, a trip full of architecture as well as much else- and this will form the basis for several blog posts. This first post puts together two buildings 'made' in London, but built in Japan. The Nagakin Capsule tower was designed by Kisho Kurokawa and finished in 1972: it provided the most minimal of dwelling standards in its capsule flats, and now stands derelict in an area of Tokyo full of new development. In clear emulation of Archigram projects done a decade earlier- Peter Cook's Plug-In City would have consisted of such prefabricated pods suspended from a service network, as Kurokawa's building does. But even closer is Warren Chalk's design for a Capsule Tower, done in 1965. However influential Archigram's work was, this is among the closest realisations of its principles- and now soon to disappear. The second building originating in conversations in London is Foreign Office Architects' Yokohama Port Terminal building, completed in 2002. Farshid Moussavi and Alejandro Zaera-Polo, then young and untried, won the competition to build this major piece of urban infrastructure in 1995: then tutors at the Architectural Association in London, they had both worked for OMA. Heralded as both a new urban type- a cruise ship terminal interwoven with a public space, an extension of nearby parks- it also represented a new architectural vocabulary of form, an unparalelled urban topography. As Zaera-Polo has written: 'the project is generated from a circulation diagram that aspires to eliminate the linear structure characteristic of piers, and the directionality of the circulation.' In other words, a complex and flowing spatial model is adopted, changing direction and level, and enabled by the use of folded steel plates and concrete girders that minimise vertical support. Space seems to drift and fold, an exciting but not disorienting experience: some have said that the built project is disappointing compared to the radical nature of the spaces as drawn. While the project perhaps promised magic, the building does realise a powerful and effective new kind of architecturally determined public space.

AA Files issue 70 has just been published, with a wealth of diverse material including texts about Robin Evans, Jan Kaplicky, Piano and Rogers and 'possible' Pompidou Centres, and Niemeyer's Copan building, among much else. There is an essay by me on the photography of Eric de Mare in relation to what was termed 'the Functional Tradition:' he travelled throughout Britain in the Summer of 1956 looking at old and completely forgotten industrial structures. This voyage of discovery of multifarious buildings including dock warehouses, mills, breweries, canal buildings and so on culminated in an Architectural Review article, and following that a book of the same name which appeared in 1958.

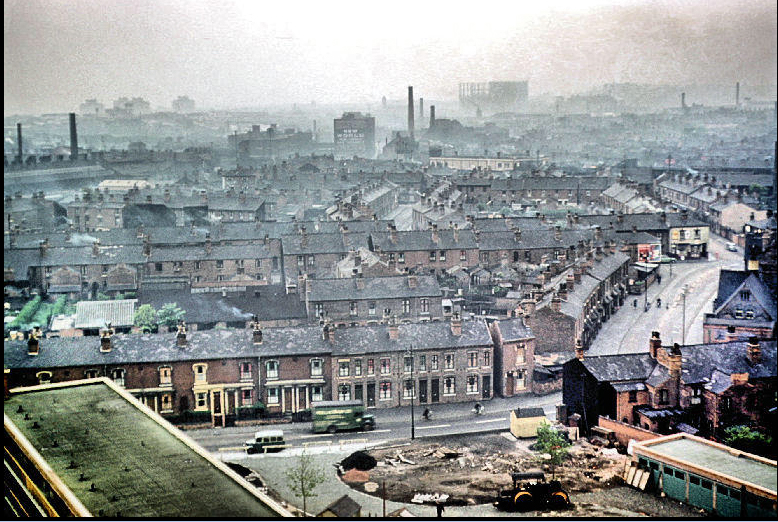

Although 'architecture without architects', to use Rudofsky's later phrase, there was much that was relevant to architects of that period, who saw these structures as expressing a refreshing originality of form not limited by traditional aesthetics. This essay narrates and interprets this body of work- which, incidentally, turned de Mare from being an architect-journalist to being a celebrated photographer- and, we hope, will also be later published in a far more comprehensive as a book. A tutor in Geography in the extra-mural department of Birmingham University, Phyllis Nicklin (1909-69) left behind for the University an extraordinary archive of 35mm slides that she had taken, to use in her classes, in the 1950s and 60s. Her subject was the city which she lived in all her life and her photographs documented the enormous changes in the city's appearance and physical fabric, as it underwent a process of transformation unprecedented in British cities. Many of the images show the nineteenth century fabric, typically of red brick terraces and small factories, juxtaposed with shockingly new modern forms: housing tower blocks, shiny office buildings, wide dual carriageway roads. Birmingham's urban renewal was going on apace. For many seeing Nicklin's pictures now, they evoke a nostalgia for simpler times of shared values and community. But however ordinary their purpose, that of a record and a teaching aid, the most compelling images picture a city in transition, in a world then filled with optimism about the modern and erasure of the outdated past. Many have an atmospheric quality, accentuated by their Kodachrome colour cast, and like the best documentary photographs transcend their matter-of-fact origin to have a significance far beyond their local context. This rich archive is the subject of a small interactive exhibition- Phyllis Nicklin Unseen- currently to be seen at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, set up by the website brumpic.com. A larger exhibition is planned, and see the archive of 446 scanned images on the Birmingham University website, at epapers.ac.uk/chrysalis.html.

My recent lecture to the AA was a reminder that many still don't know the great significance of the work of F R Yerbury in bringing modern architecture to Britain in the 1920s and early 30s. Before others whose names are now better-known, he photographed an electic collection of whatever buildings were new on his travels in Europe, almost by accident including Le Corbusier among a wealth of now forgotten figures. And he photographed the buildings of post-Revolutionary Russia as well as the American skyscrapers seen on a visit in 1926.

There's an exhibition of some of his photographs currently at the Architectural Association Photo Library Gallery, 37 Bedford Square London WC1, where his archive of several thousand negatives is held. A visit to the Venice Architecture Biennale four weeks ago has not yet been reflected in this blog- an overwhelming number of architectural ideas and installations, a mix of the predictable and dull with the truly thought-provoking. As a first time visitor, the scale of the exhibition is daunting- even a two-day visit can't include everything on show, especially in the seemingly infinite space of the Arsenale building. An approach critical of the modernist hegemony- related to the theme of Absorbing Modernity- is adopted in many of the national pavilions, including the British and French. Despite the familiarity of much of the material in the British show, the clear theme of a failed utopianism came through with invention and wit: the French did something more deeply critical and sometimes moving with a related analysis of post war architecture. Some were just wrong- the Swiss and USA for example- while others such as the Danish and the Austrian were delightful. The Chancellor's 1964 official Bungalow in Bonn was re-created- 'swallowed'- within the German Pavilion's space in a discourse about architecture and representation. The installations in the Central Pavilion are a series of discrete and separately curated exhibits on individual building elements- the ceiling, the window, the roof, the stair and so on. Their content and certainly their interest varies widely, the scope sometimes too narrow, sometimes too wide, but the overall aim of establishing a discourse about Fundamentals removes the Biennale from its more usual preoccupation with the current. This, and the overall theme of this Biennale, are the work of Rem Koolhaas who once again proves to be a kind of genius with his overall direction, however flawed the gigantic exhibition may be. The new exhibition gallery on the ground floor of the RIBA Building, 66 Portland Place London W1 is showing an exhibition of the photography of Edwin Smith, best known for his evocative and atmospheric images of British buildings and landscapes, used in a series of books published by Batsford and Thames and Hudson in the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies. Weather and mood , complex compositions of elements and, often, the dramatic use of light sources give his vision of a lost Britain a very particular feeling. It's clear, even though he trained as an architect at the AA for several years, he was out of sympathy with the prevailing mood of post war optimism and practicality.

The show, curated by Valeria Carullo and Justine Sambrook, is unusual for an RIBA Exhibition in that it really is curated- the presentation and editing of the photographs, with worthwhile supporting material, makes for a show that is both inspiring and informative. It runs until 6 December. The paperback edition of Camera Constructs: Photography, Architecture and the Modern City, with additional colour pages and improved image quality, has just been published by Ashgate. It's £35, and available online for less.

Some extracts from reviews published after its initial 2012 appearance : A brim-full compendium packed with a rich variety of relational investigations into photography, architecture and urban space. This volume…opens the box that will not close again- the box in which photography is no longer one thing, but instead is many things, differing in kind as well as in degree. Claire Zimmerman College Art Association Review This volume offers an expansive range of conceptions of architectural practice- from the imagined spaces of the unconscious, to the pristine spaces of modern architecture, to the virtual fields of Google maps. This range testifies to the commanding influence photography has had on architecture. Pepper Stetler History of Photography Photography is how most architects experience other buildings, through the feedback loop of architectural journals and now the web. Higgott and Wray detail how this promotes abstracted visions of architecture while pushing inhabitation, space and materiality into the background. Eleanor Young RIBA Journal ‘A photograph is always invisible, it is not it that we see’: as its title suggests, the book subtly and consistently reiterates Barthes’ point, helping the reader to focus on the object rather than the subject of the photograph, and therefore critically establish the parameters by which architecture is judged, validated and ultimately constructed…The book is cleverly curated to offer many disparate ways to appreciate the underlying thesis, accessible to all levels of reader...a valuable contribution to the ongoing evaluation of architecture’s relationship to its favourite medium. Steve Parnell Architecture Today Malevich, one of the fundamental figures in the evolution of modern architecture, let alone modern art, is the subject of a major exhibition at Tate Modern currently and running until 26 October: Zaha Hadid has spoken about his importance to her development as an architect, which can be seen very clearly in her earlier, pre-digital projects. His Suprematist paintings- incidentally among the first completely abstract paintings- show a floating world, forms of coloured rectangles in a dynamic relationship to each other. But it is in Room 8 of the exhibition that the most exciting architectural work can be seen, and they need to be seen as their subtleties cannot be reproduced in photographs: a series of white-on-white paintings as well as two which show coloured forms in dissolution, take Malevich’s move into an immaterial world that much further. Here also is a series of ‘Architectons’- abstract white sculptures taking these Suprematist forms into three dimensionality- we see the promise of an architecture, however scaleless and unresolved technically, which show an idea of what modern architecture could have been be rather than what it was to become. And what does it all mean? Despite the date of this work in the 1910s, not much to do with the 1917 Russian Revolution. Curiously, the curators of this exhibition seem to have expunged any reference to the spirituality which shaped his work. One version of his black square paintings is placed high in the corner of a room, the place for an ikon in traditional Russian homes, in this emulating Malevich’s own installation in the 1915 Petrograd Suprematist exhibition.The white space in his work is the space of infinity, both inward and outward:going beyond the world of material into the cosmic and transcendental. And the black square, which became his personal symbol, a representation of man and his creation. |

Archives

September 2020

Categories

All

|